The History of Snack(s)

Many observers have argued that large food companies shape public opinion in ways that serve profit. A commonly cited example is Kellogg’s role in popularizing the idea that “breakfast is the most important meal of the day,” alongside the rise of mass-marketed breakfast cereals.

Of course Kellogg’s isn’t the only company to invest in shaping habits and beliefs. The pattern is familiar: corporations gain market power, and the public absorbs the downstream costs—often in health

The word snack is relatively new in usage, entering the common vernacular sometime in the early 20th century. The real acceleration in use came after World War II, when industrial food production, mass advertising, and distribution scaled up dramatically. From there, “convenience” became a business model—and a lifestyle.

Manufacturing Habits

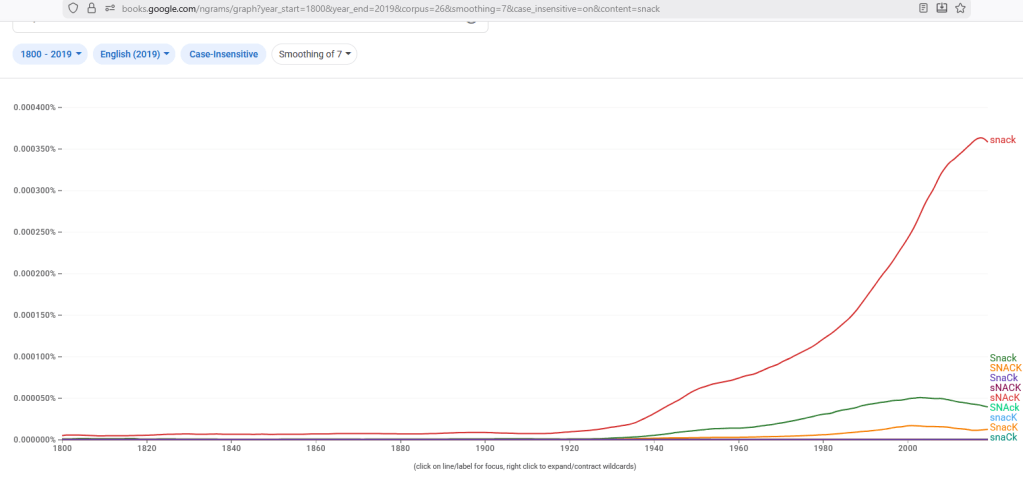

The graph below tracks the frequency of the word “snack” over time. It’s small, so here are the key takeaways.

Before World War I, “snack” appears far less often in published text. After WWI it rises, and it rises rapidly after WWII as mass-produced packaged foods and national brands become normal. By then, recognizable companies like Campbell’s, Heinz, and Kellogg’s were already major players.

The mechanism is simple: once mass advertising became cheap and ubiquitous, companies could sell not just products—but habits. “Snack” wasn’t only a word; it became a routine. And routines structured around consumption are profitable.

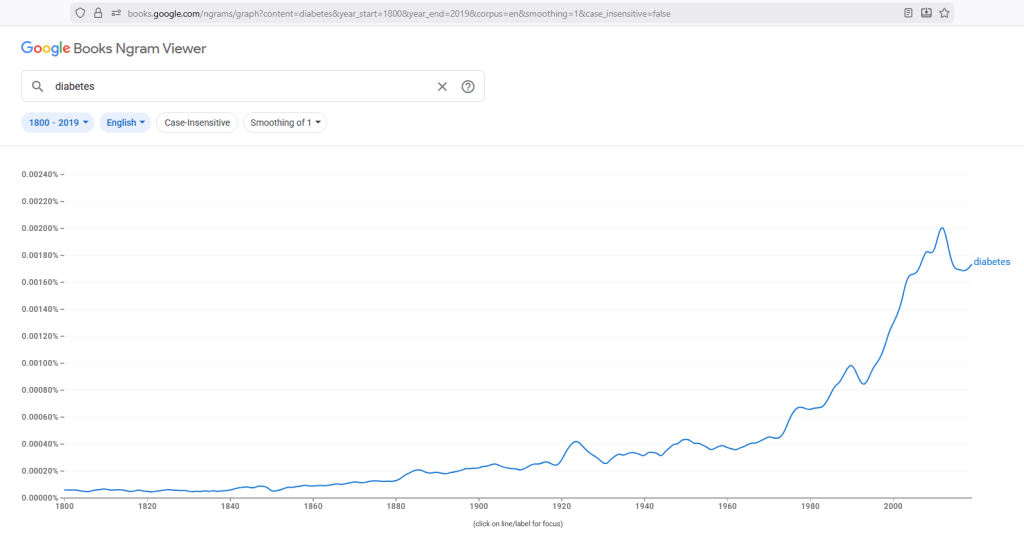

If this feels like a leap, look at the health outcomes in the West. To keep it concrete, here’s a second graph: the rise of the word “diabetes.”

The curve for “diabetes” rises in a similar direction over the same period. It’s not proof of causation—but it’s a clue about what changed culturally and biologically.

To be clear: I’m not claiming snacks cause diabetes. I’m pointing out something simpler—snacking was marketed into normal life, and it usually means extra calories from low-nutrition foods. Pause for a second: what foods come to mind when you hear snack?

What I’m really asking is this: where did our eating habits come from—our bodies, our family, culture… or an advertising budget? Because a lot of us stay loyal to brands that aren’t loyal to our health.

You might disagree, and that’s fair. But here’s the question I can’t shake: if you wanted to eat real, high-quality food consistently, could you afford it? If not, that isn’t just “personal choice.” It’s a machine that is broken. It is a system that convinces us to make choices that are not in our own best interest.

Stay Wild!

Image credit: “Froot-Loops-Cereal-Bowl” by Evan-Amos is marked with CC0 1.0.

Leave a comment